Nigeria: MLT political risk rating upgraded from 6/7 to 5/7

Interventionist economic policies are likely to continue

Nigeria is Africa’s biggest oil producer and has the largest proven reserves in the region, after Libya. Not surprisingly, the country is very reliant on the oil sector. In 2018, oil accounted for 62% of exports and 58% of government revenues. The lack of diversification exposes the country to the risk of fluctuations in global oil prices and oil output disruptions resulting from instability in the oil-producing regions. The fall in oil prices – in combination with years of mismanagement – hit Nigeria particularly hard in 2016. The country is still recovering from this oil price shock (see graph 1). Real GDP growth of respectively 2.3% and 2.5% is expected for 2019 and 2020, a rate below population growth. President Buhari’s response to the oil price shock was the introduction of interventionist economic policies. These policies, however, hinder economic growth and restrain foreign investment. Indeed, capital controls and the Central Bank of Nigeria’s interventions obstruct transfers and limit foreign exchange availability in the market. In addition, import restrictions on a significant number of goods still cause disruptions and supply shortages. For example, Buhari's government promoted a nationalistic vision of agriculture self-sufficiency in the production of rice, millet, sorghum, maize, soybeans and wheat. Ever since, agriculture GDP growth has slowed while the output gap encouraged informal food imports (smuggling) and hikes in food prices. As Buhari won a second four-year presidential term in February 2019 by a decisive margin, these interventionist policies are expected to continue.

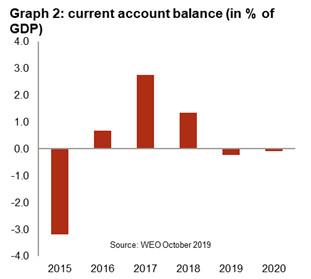

Liquidity position has strengthened but remains under pressure

As illustrated in graph 2, the West African country experienced a small current account deficit in 2015, followed by a surplus in 2016-2018; and it is set to reach a minor deficit over the coming years (of about -0.1% to -0.2% of GDP). Whereas gross foreign exchange reserves were under severe pressure in 2014-2016, liquidity levels have recovered supported by higher oil prices, large Eurobond issuances and the fact that more hard currency is available in the market. More recently, volatile hot money inflows have also been feeding liquidity levels, although these speculative capital flows incite market instability as they move very quickly in and out of the market. The improved liquidity situation led to an upgrade of the ST political risk from category 6/7 to 5/7 in June 2018. That being said, the official naira is not floating freely and is kept stable around 305 naira/USD by selling foreign exchange. This is putting Nigeria’s liquidity under constant downward pressure and causing exchange-rate misalignment. Especially as the current account balance is expected to be in negative territory in the coming years, the naira peg and foreign exchange reserves will remain under pressure. As a result, foreign exchange reserves (standing at 5.5 months of import cover in October 2019) are likely to shrink in the coming months to years.

Public finances are relatively healthy

Inflation has fallen since the 2016 peak (18.5%) thanks to tighter monetary policies, although it remains above target (projected around 12% in 2019 and 2020). This is partly explained by the central bank’s continued fiscal deficit financing. Nigeria’s fiscal deficit is expected to be slightly above 4.5% of GDP over the next few years, leading to a steady accumulation of public debt. However, thanks to the country’s very favourable starting point (public debt at 27.3% of GDP in 2018), total public debts are only projected to reach a sustainable 36% of GDP by 2023. Nigeria’s main fiscal weakness lies in its government-revenues-to-GDP level, which – at around 8% – is among the lowest in the world. It is explained by the limited non-oil tax base, lower oil revenues since 2015 and weak institutional capacity. This reflects the failure of subsequent governments to implement vital structural reforms. It also poses severe risks to domestic-debt obligations as limited revenues frequently lead to a significant accumulation of public arrears. Nonetheless, the long-term fiscal indicators are favourable in general.

Limited financial burden

Nigeria is enjoying a low external-debt level compared to the size of its economy. In 2014, external debt was estimated at 8.3% of GDP in the latest IMF report of April 2019 – a very low level. External debt has swollen in the past years owing to debt issuance and the weakening of the naira in 2015-2016. That being said, it was projected at around 16% of GDP at the end of 2019 – still a low level. In the coming years, nominal external debt is likely to continue to grow, mainly due to public-debt issuance, but below the level of GDP growth. Therefore, the external-debt-to-GDP ratio is likely to decrease in the coming years. In addition, the external debt service poses a limited financial burden. Indeed, despite the severe terms-of-trade shock and obvious difficulties confronting the country, Nigeria has managed to keep its medium- to long-term debt profile at sustainable levels.

Manifold internal conflicts remain an important weakness

There are still many conflicts within the country, driven by multiple factors. Firstly, ethnicity remains an important driver of conflict. Nigeria is one of the most ethnically and linguistically diverse countries in the world with over 300 ethnic groups and over 500 different languages. Secondly, religion is an important fault line in the country. Muslims live predominantly in the north and Christians mainly in the south. Boko Haram – an infamous example of a religious conflict – continues to destabilise the northeast. Furthermore, under an informal agreement between Nigeria’s rulers, the presidency has rotated between the Christian south and the Muslim north. While it has no legal standing, any attempt to violate it could stoke political tension. Thirdly, climate change is also an important source of conflict. The rapidly increasing desertification (in combination with ethnic tensions and poverty) has led to conflicts between farmers and nomadic herders in the Middle Belt, which have been intensifying in the past years. In addition, oil exploitation and revenue sharing in combination with the pollution of the environment have frequently been a source of friction as illustrated by the regular Niger Delta pipeline attacks. Lastly, pressing social problems, including the huge youth unemployment and poverty, increase the security risk in general as demonstrated by the many kidnappings, omnipresent banditry and cattle rustling in the country.

The lack of viable long-term solutions and rising demographic pressures – Nigeria is Africa’s most populous country – mean occasional reciprocal bouts of violent unrest are very likely. It remains to be seen whether sufficient government resources will be made available for stemming the surge of violence. The numerous security crises seem to be beyond the federal government’s managerial competence due to endemic corruption and the absence of government control in several regions of the country.

Upgrade of the medium- to long-term political risk classification from 6/7 to 5/7

The country’s reinforced liquidity position in combination with the ongoing low external debt-stock and debt-service ratios, have led to an upgrade of Nigeria’s medium- to long-term political risk classification from category 6/7 to 5/7. That being said, the fragile political situation, interventionist policies (import restrictions, capital controls and exchange-rate misalignment), overreliance on the volatile oil sector and severe security risks still pose important weaknesses.

Analyst: Jolyn Debuysscher – j.debuysscher@credendo.com